“A new scientific truth doesn’t triumph by convincing opponents and making them see the light, but rather its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”—Max Planck (1858-1947), German theoretical physicist, discoverer of energy quanta and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

It seems like I keep having the same two conversations, be they with people around me or inside my head. Both conversations related to and extend from one another. Neither comes first though they have a sequential relationship; if you start with one, you’ll probably find yourself asking the other no matter. So it’s really just one big issue centered around two parts:

1) Is it “and/both” or “either/or?”

2) Can meaningful change happen from within or must it happen from without?

Whilst most of my articles pertains to learning and education (which aren’t the same thing), the two questions above are fundamental when considering any socio-economic, political, or culture change. In fact, great women and men have posed these questions for thousands of years. We could fill countless pages with examples of incremental and revolutionary changes, of changes initiated by or resulting in violence and non-violence alike, of changes coming from the top, the bottom and the outside. In each case, on consciously-strategic or unconsciously-reactive levels and everywhere in between, people have had to ask whether they can get along inside the system or whether they need to break or leave it. There is no one answer, there are only perceptions and those perceptions lead to positions, actions, and outcomes.

Different perceptions are what lead to the tension between progressive and traditional outlooks on education. Yet the progressive-traditional continuum is an outdated paradigm, just like the one in politics between Left and Right. Both are vestiges of the 20th century and these lenses are no longer useful. I am happy to have this conversation at another time, as it requires more than I can give in this article*. The point is that we should move beyond the continuum of progressive-versus-traditional education (PvTE), which is no longer useful to address the challenges of the Anthropocene.

We need to move beyond the progressive-traditional continuum view of education because it asks questions that will not solve the problems of the Anthropocene, which include climate disruption, socio-economic injustice, and the precariousness of our relationships with other living things. The PvTE framework is a product of humanism, which is largely guilty for the problems we face in the first place. Let’s unpack this.

One of the main areas of contention within the PvTE debate is the role of assessment of skills and competencies. It’s not the only one, for sure, but it’s one that encapsulates the debate.

I’m grossly over-simplifying here and surely someone will say that I’m being flimsy and that assessment is way more complex. Yes, they’d be right. I’m butchering complex ideas in order to open up thinking rather than reflect realities that can never be perfectly reflected. All models are inaccurate, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be useful sometimes. By tackling the beast that is assessment, we are putting the model through a test.

On one side are the traditionalists, who believe (generalizing) that students should demonstrate acquisition and mastery of certain sets of required knowledge and skills through standardized experiences. This standardization allows students to stand apart from one another based on what are supposed to be reliable and valid measurements. At the heart lies a belief that meritocratic hierarchies are fair and effective ways to organize society. Everyone has the opportunity to show what they know and can do based on a system that allows comparison of results, which helps with triage when it comes to university and work life.

On the other side are the progressives, who believe (generalizing) that education should center around learner agency and allow each learner to demonstrate their understanding in ways that meet their needs and interests. The role of school is to prepare learners for a volatile and uncertain future, equipping them with skills necessary to succeed in a world we cannot yet imagine because of the speed of change. Progressives don’t discount content, which should fit the needs of the child, and sometimes that means exposing the child to a certain defined curriculum, but this is meant to equip the child for success rather than the need for her to acquire specific sets of knowledge. Lastly, most progressives agree that skills and competencies also involve essential skills such as critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication and that these need to be developed and assessed.

The problem is not where one lies on the continuum, the problem is that the continuum itself is the product of a humanist worldview. Humanism puts the individual at the center and (too often, not always) perpetuates a Cartesian binary between mind and body, reason and emotions—not to speak of spirit. This prevents us from connecting with others and seeing ourselves as part of one whole. By emphasizing the importance of the individual, humanism atomizes us, disconnecting us from the network of vitality, separating us from all other life forms and the Earth. This will not help us solve the issues of the Anthropocene: climate disruption, socio-economic injustice, and the precariousness of relationships with other living things.

No matter where it lies on the PvTE continuum, humanist assessment as a whole emphasizes individual skills, be they “hard” or “soft.” Even when students work in teams, there is a greater emphasis on individual development than what the team was able to produce. I’m not suggesting that this is wrong when we think about doing what is right for the child. I am proposing that what we assess misses the mark because humanism’s centralization of the individual means that does not connect the individual to the outside world. The tree blocks the forest, or more to the point, the forest ecosystem.

The vast majority of assessment frameworks don’t take into account how we put these skills into action. Sure, there may be reference to service and action, but how often is impact of service included in assessment? How often is action a self-congratulatory byproduct that makes us feel good but keeps the student at the center and those who benefit from the action at the periphery? The reality is that in most cases, the focus remains largely on skills, and action is an afterthought. That is why assessment in most schools is stuck in literacy and numeracy levels, how well a student is able to extract information from a source, or whether the lab report had the correct format and citations. Not always, of course, but ask yourself how the data in most schools are collected, organized, and (if you’re in a strong school) disseminated for learning. There will be outliers, but the data are skills based, not impact-based. Look at websites and reports that claim to outline the world’s best and most progressive assessment practices. How many push to create experiences and outcomes that have purpose and “do good” in the world? They’re almost all student-centered with little to nothing about the effects of putting those skills to use, for good, for the community.

Measuring skills doesn’t tell us anything anyway. It’s action that matters. Skills do not exist if they cannot be applied. They remain in your head, untapped potential energy. It is only when this energy is released through action that it becomes kinetic energy. Project-Based Learning is one of the best ways of transforming that potential energy and is a wonderful step forward to deepen learning and create transdisiplinary connections. Yet for PBL to be transformative, it needs to go beyond projects and the assessment of individual skills. It needs to have purpose for the welfare of the self, others, and the planet—the bio-collective.

Kinetic energy is not enough either. Kinetic energy is used by all things, living and non-living and does have impact, but it is not intentional**. In Newtonian physics, a billiard ball transfers kinetic energy onto the ball into which it collides, propelling the latter through the a very close to elastic collision. This propulsion is the impact, but the cue balls don’t possess consciousness so there is no intentionality. We could take this further and suggest that skills are only probabilities until they are observed (through action, not skills as probabilities), taking us into the layperson’s realm of quantum mechanics.

We need to focus on the quality of the impact—the transfer of the kinetic energy—in terms of intention and how consciousness shapes outcomes†. Instead of assessing skills, we should consider the impact learners have through their actions, how their thinking, initiatives, projects, reactions, relationships, curiosities, acts of kindness… affect all living things (humans included!—the bio-collective). That is what matters. The quality of impact to benefit other life forms.Impact is what happens when you do something with your skills and you increase the quality of impact by developing the right skills for the job.

This approach not only gives our actions purpose, it forces us to see beyond the duality of I/you, me/them, this/that. Prioritizing positive impact on others (as well as the earth and ourselves) as the purpose of learning and action removes the learner from the center. The learner is no longer isolated, but rather takes her place within the larger ecosystem, connected to the bio-collective. This is the shift: when we focus the positive impact of our actions, we understand we have a common purpose, which at its most basic level is the healthfulness of the planet. This means we stop thinking in terms of assessing individual skills and start thinking in terms of commonalities in action. We are the whole and we have impact on the whole.

Humanism (and its cousin anthropocentrism) gives way to something else, a post-humanist conception of the world where there is no binary between the individual and the whole. From this blue sky, needless to say, assessment in its current form melts away.

This doesn’t mean we stop assessing learners’ mastery and understanding of concepts, content, and skills. It just means that we assess these things insofar as they inform us on what learners need to tackle and master in that moment and in the future to maximize the positive impact on the bio-collective. This adds a dimension to assessment for learning. You cannot measure an arrow’s position and its momentum at the same time. We are interested in momentum not a snapshot.

Impact is the next step in authentic assessment. We cannot stop at measuring whether a student has proficiency in certain skills or has acquired certain knowledge without actually requiring them to do anything with them. You may get an A on your test on the quadratic equation, but if you never use the QE, what’s the point? You may as well have never heard of the QE, it’s all the same.

Even if we required learners take action, this extent to which this action impacts others matters is critical. If Leonardo da Vinci had locked up the Mona Lisa in his basement and no one had ever seen the painting, its revolutionary style and artistic techniques would all have been for naught (and thus not revolutionary) and it would have been like they never existed. They would have had no impact. That is why the Nazis burned books, to prevent ideas from spreading, to suffocate the ideas’ impact. They couldn’t care less whether the books met set standards for writing persuasive texts††.

Assessment is just one level. From there we can emerge into a broader system of values, and ethics, one rooted in post-humanism. We would avoid getting stuck along the PvTE continuum, which we would leave behind. The humanism from which the continuum was born has as its very essence a quasi-religious belief that the needs of the individual come before those of the whole§. Witness humanism’s extractive tendencies, its neoliberal agenda, its hierarchization of species and individuals. We need a learning ecosystem that goes beyond with humanism toward a post-humanist, post-anthropocentric, regenerative, and socio-economically more just system where we are all learners, pulling together for the welfare of the community, of the bio-collective.

What if we opened up education to the entire community, made it a community affair? What if we created reciprocal relationships at all levels, between young learners, humans, humans and the natural world, and so forth? What if we developed a set of ethics for the Anthropocene: “practice eco-reciprocity,” “stand up for justice,” “share with solidarity,” and “act with kindness?”

What if we left behind the current education system, the one that is just fiction anyway because it tells the story of the Industrial Revolution, not the stories of societies past or our relationship with the Earth?

What if we learned for purpose? What if that purpose was the driving force for a culture of action? What if everyone in the community participated in learning, thinking, and action, coming together for impact?

Sure, at first it would start small. Let’s think of an example.

Imagine we find out there is a group of learners who love cats and we know that there is a stray cat problem in the area. One can co-create a project (with the students’ buy-in and full participation) with purpose from these interests and community context. For instance, the learners could collect data to help animal welfare organizations with “trap, neuter, and release” initiatives. They could collaborate with vets and perhaps local officials and neighborhood organizations. The students could also connect with labs and pet supplies companies, perhaps even think about building shelters, opening conversations with engineers, tradespeople, and the local makerspace, if they are lucky enough to have one. All of this supported by coaches (formerly known as teachers) from several disciplines, because this project extends across so many disciplines.

Everyone in the community would come together for a purpose, helping stray cats.

Imagine now a community with no spatial constraints. Imagine taking the community online, meeting and interacting with people across the world through similar initiatives and learning from one another. The school is then an engine for connections.

Driven by purpose.

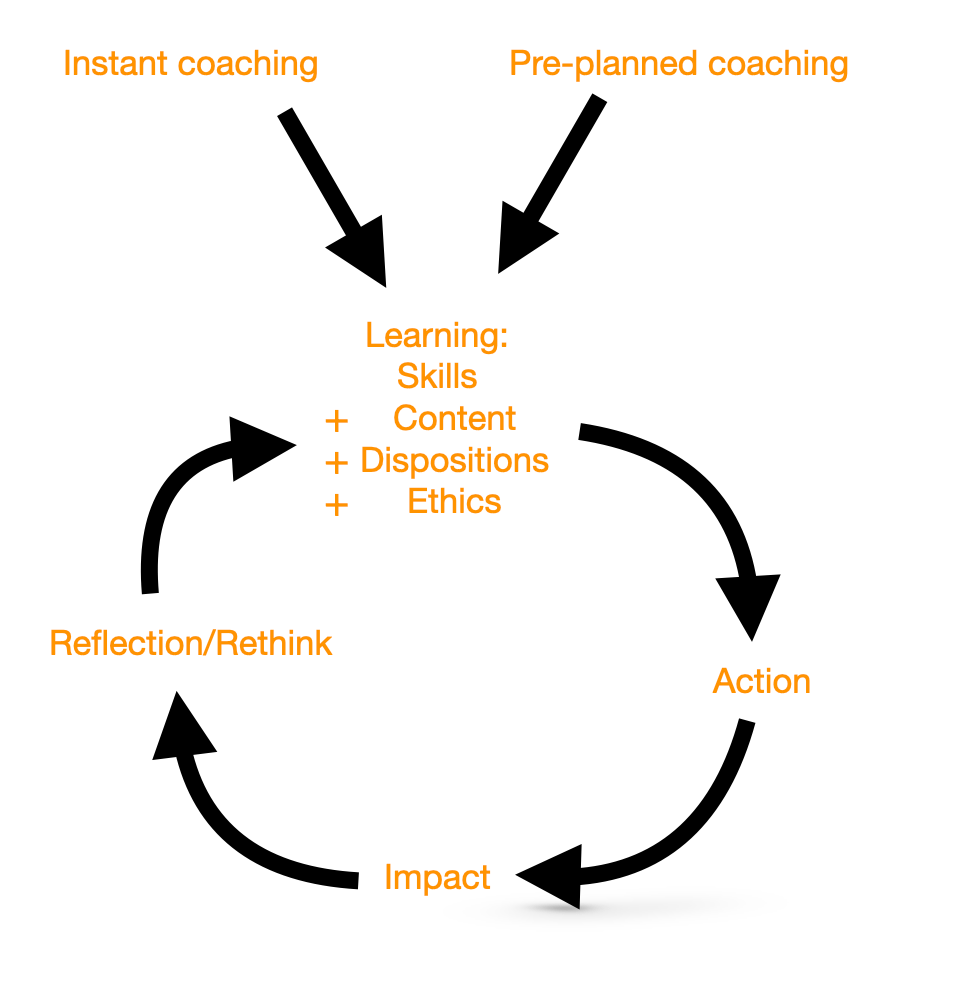

Coaches develop learners through skills development both on the spot and in more planned ways. Skills are put to use in action, for purpose. The impact of our actions toward the collective purpose is all we need to know and we can reflect on impact to hone our skills, content knowledge, dispositions and ethics. Maybe it could look like this:

This new model emphasizes impact and purpose, and breaks open the learning ecosystem to the entire (local, global, and virtual) community—rather than have skills, content, and even individual interests atomize education into isolated students. It lies beyond the PvTE continuum because it values purpose and the collective over the individual, the whole over the parts. It is beyond what we know because it leaves humanist values behind.

This new model goes beyond school.

Going back to the conversations I have been having, going beyond school means that we go beyond the dichotomies too. It’s not “and/both” and “either/or.” It’s both “within and without.”

When you find yourself in a new space, you do not operate within the same constraints. Let’s create a space beyond the PvTE continuum. No one is excluded. Everyone can join. All you need is a belief in adopting a post-humanist approach to living, learning, and thriving, one that sees the complete interconnectedness of the world, where we are all part of one whole, where all life forms have value and worth. It is a way of living that blends aspects of ancient wisdom with the biotech and datatech revolution. It is knowing that it will take time to eschew anthropocentric behaviors and attitudes, but doing so is critical to meet the challenges of the Anthropocene.

I could have started the article with Buckminster Fuller’s words: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

We need a model beyond school.

* The terms Left and Right originated in the French Revolution. In the hemispheric seating arrangement of the Chamber of Duties, radical anti-monarchists sat on the left of the speaker and defenders of the crown on his right. In the 20th Century in France, where politicians sat depended on their political party, whose base was drawn largely along class lines: Communists sat on the far left, Socialists a bit more toward the middle, and the National Front (or another nationalist party of earlier times) sat on the extreme right. Whether this configuration still stands matters not. Today, there is no Left and Right in post-industrialized countries. The educated, middle, and upper classes (up to but not including the 1%) tend to vote largely for parties that were traditionally working class parties in the 20th Century (Labor, Democrats. Socialists). Traditionally conservative parties (Tories, Republicans, Gaullists or National Front) now attract voters who hold fewer, if any, diplomas and who have lower incomes, those considered in the past working class. Look at the income and education demographics of voters for Biden and Trump. Look at Marine Le Pen’s electoral base. This does not make sense in a traditional Left/Right worldview because it contradicts class interests. A post-Industrial society requires a fresh set of demarcations. Daniel Markovits and Thomas Piketty outline this in convincing empirical, but you can find information on correlation between levels of education and income with voting patterns many places on the web.

** Annaka Harris describes how plants will exchange nutrients with other plants of the same species if one amongst them is undernourished. This pushes the bounds of how we understand consciousness. This is all new territory for me.

† Maybe using concepts of free energy as a basis? Let’s continue to think about this.

†† Of course Plato would say that the ideas were still out there to grasp, books or no books.

§ Clearly, this doesn’t apply to Fascist or Communist derivatives of Humanism, but they’re not so prevalent anymore.

There are lots of things to consider. I am still thinking about it too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like the idea that learning goes beyond school. I’m getting used to this bio-collective idea as well. In the example of the cats learning situation, however, I have a question. When you coach the learners into undertaking this project, do they have the freedom to say “no, I am not interested.” Freedom is my big bug. I really want to give students the opportunity to live, grow and learn in freedom.

There is another dimension the cat situation that preoccupies me. You imagine the students talking to a range of different community services. It seems pretty clear to me that some of those services require a higher level of formal education than others: lab work vs cat rescue, for example. How do you get around this?

It seems to me that if you do not have some kind of assessment at an individual level you have no way of verifying training. I really want a qualified lab technician to do lab work and I don’t care about the qualifications for someone who rescues cats.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jason Preater I should have been more clear (will make edits), yes they students say yes to the project and are consulted. Teachers should be connectors or maybe facilitators of idea generation. Thank you for pointing out the need to specify.

I guess the lab work would depend on age and levels of development. Middle schoolers should be able to do some work in labs, PS students too. Maybe it’s at the right level of challenge. In fact, it opens up the door to the idea of playing and experimenting in a lab (in the safe, curious way under supervision) rather than relocating experiments. You need both but then let’s make sure yo do both.

Yes, definitely I’ll tighten up the text.

And you’re right about assessment. Lab work same as for driving. It’s not as easy as I wish if were but it could also be a question of multiple levels of assessment, including impact on all this.

On a football team, you assess your players’ skills and position them based on those and pull together for a common purpose, the match.

Thinking this through.

LikeLiked by 1 person