This article was published in IntrepidEd News on 6 January 2024.

No two persons ever read the same book.—Edmund Wilson

My grandfather passed away when I was 11 years old. He was a remarkable man, as I recall, and since I was raised by a single parent, he served as the most important male figure in my early life. At that time, I couldn’t fully appreciate, as I might now (having become a historian), just how rich and eventful his life must have been.

He was born as one of seven siblings in pre-Great War Austria. Herbert Freud emigrated to France in the 1930s to escape the increasingly obvious anti-Semitism of Central Europe. In Paris, he met my grandmother, Emina, or in her more Gallicized form, Emma. She was another recent immigrant who thought it best to leave Kishinev before becoming a victim of the next pogrom.

Herbert was a chemist who held several patents for processes related to the corrosion resistance of metals and alloys, particularly iron and zinc, through phosphating. He was also a member of the French Communist Party. During the Occupation, the Party provided him with fake identity papers, and for five years, he would be known as Jean Frasch, a German-born Alsatian goy whose mother tongue was German. This fabricated story helped explain Jean’s Germanic accent. Until the day he died, Emma continued to call my grandfather Jean.

Some time in 1942, Jean, Emma, my toddler uncle Claude, and newly born mother Jeanne crossed furtively into Free France under the cover of night, with the help of a guide who knew which passages to take and which to avoid. During the war, guides were known to double their money: money from refugees for safe passage and money from the Gestapo for delivering a group of Jewish transgressors. With effort and luck (nearly discovered sleeping in a barn by German soldiers), the young family made it to Marseille. At some point, a Communist Party friend warned Jean that Nazi authorities would be rounding up Jews the next day for deportation, and there was a good chance they would be coming by his house. The Freud/Frasch’s again escaped in the night, finding sanctuary in the homes of other Party members. My grandfather eventually left for the Massive Central to join the Resistance in 1943. I only heard bits and pieces of this chapter. I was very close to my grandfather and I can’t measure the extent to which he sowed seeds for my later deep curiosity for twentieth century ideologies and the Second World War—I wrote my doctoral dissertation on just that—and of course it had to have played a part.

I can see the chaotic traffic on the Champs-Elysées as my grandfather and I drove toward the Arc de Triomphe in his Citroën DS. The trees lined along the wide sidewalks where tables and chairs of the cafés break up the pattern of luxury stores and travel agencies. I had a sense in that moment—perhaps the uncovered memory of a show I’d seen on TV or even the traces of the collective French memory—that a conquering army had marched down this avenue. I asked my grandfather if that was so, and I can hear his reply now “Ouais, les Allemands” (Yeah, the Germans). On this very road, originally a garden promenade of Louis XIV, German soldiers marched as victors just as their grandfathers had done 69 years before, and their grandfathers had in 1815. Officers and infantrymen of three armies gazed at this same Arc de Triomphe as their boots clattered on this same paved cobblestones, under the same gray sky. I saw this in my mind’s eye.

Quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg wrote, “What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” The term “history” originates from the Greek word ἱστορία (historia), which means inquiry, and shares the same etymological root as the word “questioning.” (from Latin “quaerere” and Proto-Indo-European “k w es-,” both meaning “to seek”). History, as a discipline, goes beyond asking questions: it is an imaginative reconstitution of the past in the present, from selected events (as artifacts), re-configured so as to provide coherence and meaning to the questions we pose, themselves born of our situatedness.

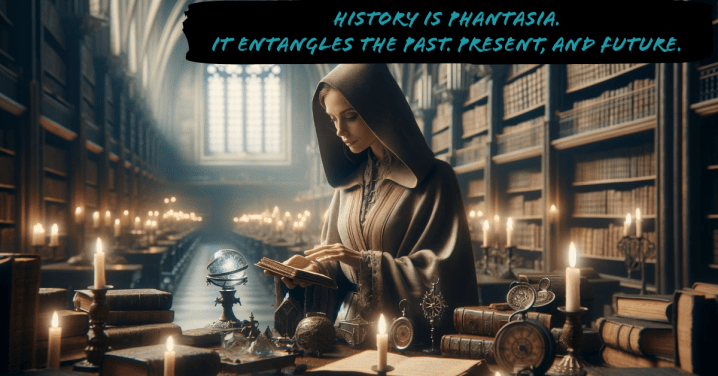

“History” is a treacherous word. Linguistically, it has nothing to do with stories, but as a practice, everything. I wish we might use another word that is more representative of what actually takes place when we delve into the past, a word that is less laborious and more playful than inquiry. I wish we could replace history with phantasia, from the Greek φαντασία (phantasia), closely meaning imagination.

History is phantasia after all, a creation from our imagination. History only begins with inquiry, which is temporarily satiated as we collect facts and organize them in patterns that we analyze, synchronize, and synthesize so as (sometimes) to explain what may have happened in the past. We lose our way when we mistake facts with Truth.

“Fact” comes from the Latin facere, which means “to make” (think, factory). Facts come from the cuts we make in spacetime to make sense of the world. We take infinite possibilities and make cuts to stabilize (make) facts. Facts are political insofar as they are born from our ethico-onto-epistemology: they are molded from our ethical commitments, ontological assumptions, and the ways we understand and perceive the world. This is why some facts are considered more “important” than others at different times in our lives and by different people. They are not real or true in themselves, but we assign them a value, and we matter them in order to create a shared understanding and meaning.

Example: The Battle of Waterloo took place in 1815. This is a fact we use to make sense of the world, but there is actually nothing here to hang onto as the Truth. The Battle of Waterloo was an event that we have bound spatially and temporally (never mind that the Battle of Waterloo is part of a longer history that extends in both directions, to and from 1815). We understand Waterloo to be a place in Belgium (another invention or concept) because we gave the place a name where before humans there was none. Its longitude and latitude are also constructs of the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE. The year 1815 represents the number of times Earth had completed its orbit around the sun since we decided that one particular revolution was more significant than any of the other 4.5 billion revolutions in Earth’s history. We called this revolution 1 CE, and it marked the beginning of the Common Era (really, the Christian Era). These are facts because we made them. They are not (absolute and monolithic) Truth.

When we study history (phantasia), we collect these facts and assign them value. We keep some and throw away others. We prioritize them, connect them, and re-organize them. We reconfigure the facts we make into something comprehensible, something that explains what we’re asking, our initial inquiry. Ultimately though, history isn’t about inquiry, it’s about the stories we tell when we systematize facts. Lest you think this only applies to history, consider Charles Darwin’s statement: “no one could be a good observer unless he was an active theorizer.”

We can’t possibly know what went on in the minds of the historical and unhistorical figures we learn about. We can’t possibly pretend to have omniscience into their motivations and desires, fears and ambitions. We can’t possibly fathom clearly into the emergence of their responses to the conditions that surrounded them. With even fewer artifacts (more facts) to collect, the further in time we look back, the harder we have to squint to make sense of the past, or rather, to make sense of our present through our storytelling of the past. History is phantasia because it is a retelling of the past through our perceptions and experiences of the present. History is past, present, and future.

I hear from here (in what is now your past) the outrage that some of you will feel (your present, my future). “What do you mean? Facts are real! They can be verified. There are some events that did happen and we can prove it!” Perhaps events did take place, but they did so in the past. In physics, there is no mathematical difference between past and future. There is only entropy—the journey from disequilibrium to equilibrium—and the arrow of time (cause and effect) appears to point in this direction because of the marks left by this (otherwise nonlinear) journey toward equilibrium. Time is conceptualized through the imprint of information left by entropic processes. In other words, the past is only memory.

As we collect the artifacts of events, we sort which ones matter most, hierarchizing some, disregarding others: “rag-pickers in the dustbin of ‘empirical data,’” as writer and philosopher Arthur Koestler wrote. Even if there was a demon able to collect the infinite number of artifacts found in infinite time and space, these artifacts would still only be a collection. Only when we make sense of these artifacts by drawing inter/intra-connections do we create meaning through systematization (systems thinking). This is our ethico-onto-epistemology1.

We employ semiotics (signs and symbols) to communicate and convey meaning, but these are transient and ephemeral, useful in the now, but not real in the sense of eternal. These signs and symbols can often be confusing and miscommunicated. Sometimes we might think we agree when we actually mis-share meaning. Sometimes, we spend too long arguing about meaning and don’t get to the heart of what we really mean. Maybe semiotics are fettered to the cognitive, and we shouldn’t rely on them so much. Maybe we should find liberation in shared feeling rather than shared thinking (see Part II of this article series).

A fact is a semiotic device (remember, it is created by the cut we make—facere). A fact is a representation of information that is agreed to be true and verifiable. The meaning of a fact is found not only in its objective content but also in how it is interpreted by individuals within a cultural or social context. A fact points to a reality, but one that must be shared for the fact to take on communicable meaning. This again is our ethico-onto-epistemology.

While there is no absolute objectivity, there is also no absolute subjectivity. Mine isn’t a call for post-modernism or moral relativism, both of which can be just as guilty of denying our entanglements and reifying our selves as separate entities. No, we are not separate. We are free to choose which moves we make, but the moves must be made within a set of rules determined by our environment. Our strategies depend on the maps we use to navigate the landscape of our environment.

Why does this matter? Because when we recognize that the knower and the known are entangled, and knowledge is always situated and context-dependent, we see our faith in historical objectivity dissipate. We sweep away the idea that facts exist in themselves, that they can be observed from a distance, and would continue to exist even in the absence of the observer. We engage in critical reflexivity and ethical responsibility, always aware of our situatedness and the consequences of our choices, which are always practices of exclusion (when we draw the lines of inclusion, something must always be excluded).

This is why history may be phantasia, but the stories that we tell matter. Critical reflexivity requires us to confront the ethical choices we make when we tell stories, with their protagonists, antagonists, plot twists and details. What do we include and what do we leave out?

What do I remember about Herbert Freud? What do I know about Jean Frasch? What stories do I tell myself? What have I included and what have I excluded from his story of inclusion and exclusion? How has my ethico-onto-epistemology selected the artifacts to bring forth? How else could this story have been told? How have you filled the gaps through your own ethico-onto-epistemology? History is phantasia.

Why does this really matter? The consecration of objectivity—reductionism, empiricism, positivism—is a lure that promises the reward of Truth, the one and only deity. It is a trap. By letting go of the delusion of objectivity, we create spaces where we become we. Renouncing Truth in favor of truths that we cobble together with what we bring with us is liberation, liberation through discovering the gaps in the in-between, those gaps so often filled with misunderstandings, conjectures, suppositions, assumptions, ignorance, prejudices, and hate.

This matters because we exit the hottest year on record and enter another that will surely be marked with more conflict: electoral, ethnic, ecological. What will happen on Wednesday 6 November? How will Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Congo, and Myanmar (and…?) ever heal? When will we cross 1.5C?

This matters because when we recognize that the past is imagination, that it is created in the present, that it shapes the future, we no longer search for absolute Truth. Rather we seek collective understanding. We open up to one another, listen, try to imagine their imaginings. We appreciate the connections and the gaps (that connect) us. We flow with time as memory rather than collect pieces here and there.

We are different, but we are one.

We are all, but not two.

- I draw heavily on Karen Barad’s agential realism in what follows.

↩︎

C’est un très bel hommage que tu as rendu à ton grand père. Merci pour lui

LikeLike